http://rage-cage.blogspot.com/2010/08/confetti.html

start there ^

---------------------------

I might have adopted some of his anger. I used to hate everything about him. I remember doing homework in the kitchen late at night. Most of the lights were dimmed, which made the room turn orange. My dad’s large ass was planted, as it always was, in his recliner. The blue fabric seat had faded from his consistent weight, and it creaked heavily when he pushed against the arms for leverage to get up. My dad, not even turning from the screen, suggested that I start running more. He asked me to get him a glass of water, as he did every night. But not just any glass of water. I couldn’t use the blue glasses, because they were horrible. And I needed to fill the glass a quarter full of ice, no more. I couldn’t stand his precise directions anymore: these are the kind of people you avoid, always water plants twice, pick up sticks before you mow the lawn, separate the forks and spoons in the dishwasher. I filled his glass with purified water, let a drop of spit fall onto the ice, and stirred it with my dirty finger.

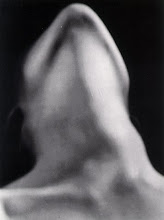

I used to look at the window in the TV room to see in the reflection what he was watching. I wanted to hate what I saw. Most times I saw a distorted nature show, or re-runs of the Andy Griffith show. The colors and shapes disconnected, skipped around on the window. A few times I saw blurry images of naked bodies. A bare chest would dance across the square reflection, two mouths would meet, their sharp features making them look angry. I would pretend to do my homework, push the end of a tough eraser onto my forehead, and watch the artificial pixels dance across his large square glasses. It was as if he turned his head just right, they would arrange to form a picture.

-----------------------------

{so it ends.}

http://rage-cage.tumblr.com