The family moved from Alabama to Tallahassee with two brand new state jobs, four young kids, and a dark two-story house. They had moved in about a year prior, and Nellie had yet to unpack her past life. Large pale wicker chairs sat facing each other in the hallway, crates and boxes were stacked to form monuments in corners, and a fabric chair cradled past-due bills and delinquency notices.

I never knew what to think or say around Nellie. She had a way of taking up an entire room with a story. Her large arms waved around, her faded mu-mu flapping with her, and her eyes bulged to punctuate a funny line. Nellie was almost a fixture in the living room. It seemed like everything in the house slowly crept toward her cracked couch. The burgundy phone sat on the large arm, three crates of home-recorded late night television shows were stacked on one seat, and tiger-tail rested permanently on the top of the tall seat, one cream colored leg pointing down.

I’d never known why, but for whatever reason, Nellie’s junk hadn’t made its way through the sliding glass doors and onto the back porch. Maybe she thought the grey screened walls wouldn’t prevent her incomplete collection of stackable dolls, or her piles of Disney themed plates, from being destroyed. Maybe she even thought they weren’t garbage already. The empty space tucked away behind the house was a place where Emily and I didn’t have to tip-toe past her crazy mother, or crawl under tables that held her baggage.

Emily had snuck into the kitchen and brought back a small yellowed broom. We spent all day sweeping up clouds of dust and dried up leaves out the rickety back door. Every day that my mother dropped me off at their dirt lawn, I would bring something to our porch; a tiny wooden alligator in my pocket, a deflated beach ball in my backpack, or a small fuchsia mirror with jewels imbedded on the back. I never felt such ownership toward a place before.

My house was so small that I couldn’t even call my room my own. Tip-toeing down the hallway would only lead me into a room full of people. Once I tried hiding in the formal living room, just to see if anyone would notice, but the open doorways left nothing a secret.

Nellie kept to herself inside the dark house, peeling price tags off of wrapped movies with chipped crimson nails. Sometimes Emily and I would lie out on the porch on our backs, watching gusts of wind slowly turn the dusty overhead fan, and make up stories. We pretended we were gypsy children on the run, or detectives outsmarting bad guys. My favorite times out there were when it stormed. The back door of the porch would rattle and slam and the sporadic wind curled around my thick hair. It almost felt like the swirls of wind would hug me by my waist and fly me right out of there.

Everything changed when Nellie lost her job at the school. My mother was making dinner when I asked her what happened. Without turning as she reached for a spice jar she said “it was just too stressful.” I was still too young to understand.

The next time I went over to Emily’s house, the bulky tanned armoire had been moved out to the porch, leaving a clean rectangular stamp where it once sat. There was a gaping hole, revealing our secret hideout. Nellie told us that enough was enough, it was time to unpack. When I went over, Emily and I spent hours moving boxes and crates. Nellie would sit on the faded wicker chair, her fatty lap filling every spot on the seat, and point with a painted nail to where she wanted a plastic crate moved to.

One by one, we moved piles of garbage from the house to the porch. Old mirrors and tall doll houses blocked out the screened walls, broken chairs cluttered the floors. Emily and I would still squeeze out there, crawling over boxes to find a clear spot to sit in, but the junk blocked out the pulsing wind and the blinding light.

Emily’s family moved from that house after a few years. They moved every year until Emily graduated. Always packing and unpacking.

Nellie must have imagined that what was missing from her life was tucked away somewhere. Maybe under an economy size pack of toilet paper, maybe in the back of a cabinet overflowing with papers. If she could just find it then everything would be fixed; no more declarations of bankruptcy, no bills or fits of anger. Emily and I shared a place once, where I felt like I could help her escape the demons of genetics. She always told me that Nellie used to be beautiful; she even tucked away her parent’s wedding photo.

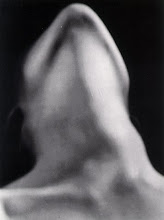

Emily traced the sharp line of her mother’s nose, her face 100 pounds lighter, and repeated “she used to be beautiful.”

No comments:

Post a Comment